BETTER DAYS FOR MOIRA

In early September 2015, an image changed the perception that the world had of the drama of refugees from the civil war in Syria. The Turkish photographer Nilüfer Demir found herself facing the body of a dead boy floating near the tourist beach of Bodrum. As police removed the body, the photographer took several shots coldly showing the victim of an improper, unjust and unbearable death.

We are used to the constant trivialisation of death and extreme pain by the fiction industry. But it is a consensual violence, accepted and conventional, while the body of a dead child lying on the ground is beyond acceptable convention. It is, in other words, a violent violence, which as a symbolic boundary of what would be accepted as understandable, has made many people wonder how this could possibly have reached this point?

One of the many people in which this image aroused an inevitable feeling of empathy was the Chancellor Angela Merkel, who a few days later declared that Germany was prepared to welcome as many refugees as wanted to live there. That decision involuntarily provoked a calling effect and in the months that followed, eight hundred thousand people, piled by the mafia into overloaded boats, crossed the few kilometres from the Turkish coast to the nearest Greek islands.

of them negotiated the channel separating Ayvacik from Lesbos. Four thousand drowned. Little Aylan Kurdi, was one among the many who lost their lives at sea, but the extreme solitude of the boy lying on the sand, had already gained a life of its own.

Mytilene Airport (Lesbos) 14th January 2016

Uxval ran his hand over his shaved head, did up his navy blue leather jacket and crossed the arrivals and departures lounge, his dark eyes checked out the premises and straight away spotted a slim man with a trimmed beard and a pink scarf who was giving him a welcoming smile. It was Stavros.

In Skala Sykamenia

After a while the boats began to arrive. An easterly wind was blowing that bode no well. “Today many more will come. The mafia are having a sale. It will be a busy day” Stavros observed.

They went down to the dock and got on Stavros’ boat, and he started the engine and with a quick manoeuvre he sailed out of the port. The boat leaped like a runaway horse.

After a minute of riding waves they were approaching the pneumatic boat that was about to sink. Uxval was right, nobody had ever taken those pictures before. They sailed round the boat in a circle, holding the rudder firmly. Uxval shot photo after photo in a frenzy. The refugees were terrified, Stavros had no camera to separate him from that terrible reality, and he could see the naked truth. And the eye contact was overwhelming. “Get closer” Uxval kept saying to him.

Uxval tried to sleep in the room next door. His arguments were unquestionably rational. He went through the shots of the day. There had been some good ones and the odd exceptional one, it had been worth risking two lives and ignoring the poor refugees, who were waiting, trembling, for a rescue that didn’t happen, while he had taken photos, as was his duty.

He smiled. It wasn’t that serious. It wasn’t his first time and it wouldn’t be his last. When the helicopter that was evacuating injured civilians fleeing from Isis was shot down, he had also taken a questionable decision. He managed to persuade the pilot to re-enact a simulation of the scene, delaying that flight to the hospital, for what would be his most famous video. Damn it, he said. The world had to know. The photo that Robert Capa took of the Falling Soldier who died at Cerro Muriano was also a montage. And he went to sleep.

Molivos. The kiss of death

The next day they went down to have breakfast at To Kyma. The port was reliving the tragedy. Some men were talking hurriedly. Stavros reported… “A large fishing boat that set sail last night from Ayvacik with the hull packed full of refugees, the engine stopped and it has been drifting near Molivos.” When it was spotted and the rescuers were arriving, part of the deck, filled with water, fell on those who were piled up inside the hull.” “There are many dead, many of them children. The Turkish coastguard have done nothing and the Greeks are not equipped for this, they are deep-water boats. There are still a lot of people on board the ship, which is practically stranded on a reef near the coast. They have asked for volunteers to go in their boats.”

“Let’s go, Stavros” “Yeah, let’s go”

They boarded Hotel Gorgona’s boat. A volunteer joined them who said he was from the Bolivarian Brigades or who knows where. The site of the tragedy was a couple of miles from Skala Sykamenia, following the coastline towards Molivos.

When they arrived, the scene was dantesque. The fishing boat was already secured and crowds of men were towing it towards the coast, laden with corpses, which the rescuers and volunteers started to cover up. Many life jackets were floating in the sea.

The problem was how to get on board the boats. It was too difficult for the jet skis and every minute someone was throwing himself or herself overboard in the hope that they would be saved, believing in the efficacy of the life jackets, which were in fact useless. They got as close as possible. Stavros and the son from the Hotel were throwing lifesavers and ropes to those who were closest to pull them onboard with their arms, while the guy from the Brigades took charge of the rudder.

They had got one man on board and the boy from the hotel was trying to revive him. Uxval was taking the best photos of his life, when suddenly… Stavros was trying by himself to pull out a boy who was a dead weight. The old photographer tried to get up to give himself more leverage, he wobbled a few seconds against the railing of the boat flapping like a great seagull, until he lost his balance and fell precipitously into the sea. He surfaced for a moment and then sank again.

The son from the Hotel saw it happening and called out to Uxval.

“Stavros has fallen in the water! Oh God, he’s drowning!”

The boy dived into the sea, he caught Stavros’ body, which was floating half underwater, under the arms and pulled him up. When he surfaced, he looked for the boat and saw that there was nobody to throw them a line or a lifesaver.

The boat was far away and it was awkward holding Stavros’ body. The boy did what he could while shouting desperately. Finally, the boat started getting closer. Uxval appeared over the side with a rubber lifesaver which he threw at them when they were near enough.

They started reeling in the cable to bring the lifesaver closer and between the volunteer and Uxval they managed to get them out of the water; first they hoisted up Stavros and then the young Greek.

They tried to revive Stavros but they got no response. Like other times in his life, Uxval saw that death was raising its head and there was no way out. His instinct had led him to do the right thing, but he had taken too long to listen to it. If he hadn’t taken the last photos, if he hadn’t gone to the cabin to put his camera away, if…

He had saved the shots of the day, but now, nobody could bring Stavros back to life. And this time there were witnesses. An indescribable anguish seized his soul. It was the end of his career, he thought.

He brusquely pushed aside the boy from Hotel Gorgona and desperately tried to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to Stavros. But it was in vain. The soul had left the body of the old photographer. His eyes staring like two empty moons.

© JC Roca Sans

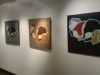

PAINTING

Aylan Kurdi

Bocetos

Making off

The arrivals

Making off

Memories of Lesbos

Horizontal drawings

Vertical drawings

Better days for Lesbos